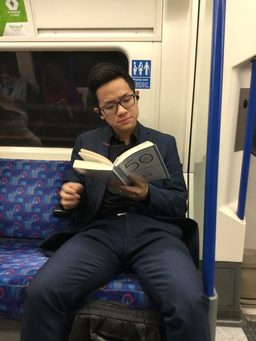

Hello. A friend recently spotted this man making his way through 50 Economics Classics on the London Underground.

Something about the pose reminded me of a painting at the National Gallery in London, 'A Man Reading' (below). Attributed to the workshop of Rogier Van Der Weyden, it was painted around 1450 and is thought to depict the Frenchman Saint Ivo (1203-53), the patron saint of Brittany, lawyers, and abandoned children. What Ivo is reading is not clear, but it is clearly a handwritten document - which got me thinking about when printing was invented.

It turns out that the painting was done at exactly the same time Johannes Gutenberg was building the first modern printing press in Mainz, Germany.

Something about the pose reminded me of a painting at the National Gallery in London, 'A Man Reading' (below). Attributed to the workshop of Rogier Van Der Weyden, it was painted around 1450 and is thought to depict the Frenchman Saint Ivo (1203-53), the patron saint of Brittany, lawyers, and abandoned children. What Ivo is reading is not clear, but it is clearly a handwritten document - which got me thinking about when printing was invented.

It turns out that the painting was done at exactly the same time Johannes Gutenberg was building the first modern printing press in Mainz, Germany.

Gutenberg trialled his press with a few Latin grammar books, but his first commercial printing, in 1455, was his famous Bibles. He sold them for 30 florins each, the equivalent of three years wages for a laborer, but still much cheaper than a Bible written out and illuminated by hand.

The 48 Gutenberg Bibles still in existence lack page numbers, indentation and paragraphing, but were the start of the modern book. Extreme measures are taken to protect them. A friend told me of a museum worker he knew who had to take an early Gutenberg book from England to another museum in Europe. The briefcase which contained it was handcuffed to the man. He would not be able to let it go without losing an arm, or his life.

The 48 Gutenberg Bibles still in existence lack page numbers, indentation and paragraphing, but were the start of the modern book. Extreme measures are taken to protect them. A friend told me of a museum worker he knew who had to take an early Gutenberg book from England to another museum in Europe. The briefcase which contained it was handcuffed to the man. He would not be able to let it go without losing an arm, or his life.

Within a few years of Gutenberg's invention the cost of books would plummet, helping to foment revolutions (not least Luther's Reformation, with its mass pamphleteering) and massively increasing literacy and knowledge for the average person. People could read the Bible, and many other works, in their homes.

This picture, 'Old Woman Reading', by Gerrit Dou, was painted around 1631. The woman, reading the gospel of St Luke, is judging by her clothing quite well-off, but not of the super rich who were once the only people who could afford to buy their own books.

This picture, 'Old Woman Reading', by Gerrit Dou, was painted around 1631. The woman, reading the gospel of St Luke, is judging by her clothing quite well-off, but not of the super rich who were once the only people who could afford to buy their own books.

Raiders of the lost sutras

Gutenberg's bibles were, however, far from being the first printed book. At the turn of the twentieth century, Wang Yuanlu, a Taoist monk, made an astonishing discovery. At Dunhuang, on the Chinese end of the Silk Road, he found the entrance to a cave that had been walled up for 900 years. The famous 'library cave' contained thousands of Buddhist manuscripts, paintings, silk hangings, embroideries and Buddha statues, but also Hebrew, Nestorian, Daoist and Confucian texts.

Gutenberg's bibles were, however, far from being the first printed book. At the turn of the twentieth century, Wang Yuanlu, a Taoist monk, made an astonishing discovery. At Dunhuang, on the Chinese end of the Silk Road, he found the entrance to a cave that had been walled up for 900 years. The famous 'library cave' contained thousands of Buddhist manuscripts, paintings, silk hangings, embroideries and Buddha statues, but also Hebrew, Nestorian, Daoist and Confucian texts.

When the British-Hungarian archeologist Sir Aurel Stein journeyed to the Mogao Caves in Northwestern China in 1907, this is what he saw:

Heaped up in layers, but without any order, there appeared in the dim light of the priest's little lamp a solid mass of manuscript bundles rising to a height of nearly ten feet, and filling, as subsequent measurement showed, close on 500 cubic feet. The area left clear within the room was just sufficient for two people to stand in.

Ruins of Desert Cathay: Vol. II

Heaped up in layers, but without any order, there appeared in the dim light of the priest's little lamp a solid mass of manuscript bundles rising to a height of nearly ten feet, and filling, as subsequent measurement showed, close on 500 cubic feet. The area left clear within the room was just sufficient for two people to stand in.

Ruins of Desert Cathay: Vol. II

Stein, something of a real-life Indiana Jones, bribed or persuaded Wang Yuanlu to give him some of the texts, including the Diamond Sutra, the world's oldest printed book (actually, a scroll five metres long, now in the British Library).

The Diamond Sutra conveys a long conversation between the Buddha and a disciple, Subhuti, on the nature of reality, including the teaching that what seems so solid and permanent to us is an illusion. Buddha tells Subhuti:

This fleeting world is like a star at dawn, a bubble in a stream, a flash of lightning in a summer cloud, a flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.

The Sutra had been translated from the original Sanskrit around 400, so the text marked several centuries of Buddhism in China, which had spread along the Silk Road from India.

The last lines of the Sutra's text state:

Reverently made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents, 11 May 868.

In Buddhism, one gains merit by disseminating Buddha's teachings, so the words "for universal free distribution" are carefully chosen. Printing meant that many more copies could be made.

The Diamond Sutra conveys a long conversation between the Buddha and a disciple, Subhuti, on the nature of reality, including the teaching that what seems so solid and permanent to us is an illusion. Buddha tells Subhuti:

This fleeting world is like a star at dawn, a bubble in a stream, a flash of lightning in a summer cloud, a flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.

The Sutra had been translated from the original Sanskrit around 400, so the text marked several centuries of Buddhism in China, which had spread along the Silk Road from India.

The last lines of the Sutra's text state:

Reverently made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents, 11 May 868.

In Buddhism, one gains merit by disseminating Buddha's teachings, so the words "for universal free distribution" are carefully chosen. Printing meant that many more copies could be made.

Another revolution

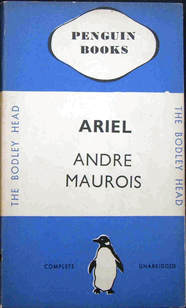

I'm interested in anything that has led to the democratization of knowledge, so it was a pleasure to read recently Stuart Kells' Penguin and the Lane Brothers: The Untold Story of a Publishing Revolution.

They are so much a part of modern life that it is easy to take them for granted. Yet starting in the 1930s, Penguin's cheap but attractive paperbacks revolutionized publishing by bringing high-grade fiction and non-fiction to the masses - a “poor man’s university”. As a brand, Penguin became so hot that its 1961 share offering was oversubscribed by 15,000 percent. The public face of the company, Allen Lane, was feted a bit like Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg is today.

I'm interested in anything that has led to the democratization of knowledge, so it was a pleasure to read recently Stuart Kells' Penguin and the Lane Brothers: The Untold Story of a Publishing Revolution.

They are so much a part of modern life that it is easy to take them for granted. Yet starting in the 1930s, Penguin's cheap but attractive paperbacks revolutionized publishing by bringing high-grade fiction and non-fiction to the masses - a “poor man’s university”. As a brand, Penguin became so hot that its 1961 share offering was oversubscribed by 15,000 percent. The public face of the company, Allen Lane, was feted a bit like Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg is today.

Penguin paperbacks ushered in one of those rare revolutions in which everyone wins: authors (because of big new audiences); publishers (bigger markets); and the public (greater literary enjoyment for a fraction of the price). Suddenly, people on low incomes could afford to buy books for the first time in their lives, instead of borrowing them from libraries. What Penguin stood for though, more than cheap books as such, was a general lifting up of the population. For this service, it remains a much-loved brand.

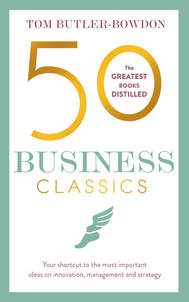

I will be including a chapter on the Penguin story in 50 Business Classics, which will be released in April 2018. There's a sneak peek of the cover!

You can preorder already here on Amazon or Amazon UK.

I will be including a chapter on the Penguin story in 50 Business Classics, which will be released in April 2018. There's a sneak peek of the cover!

You can preorder already here on Amazon or Amazon UK.

Bedside, fireside

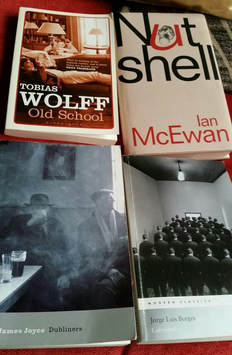

This year I've tried to read more fiction, and these are some of the books I enjoyed.

Had never read James Joyce properly before, but Dubliners was a revelation. Written when he was in his twenties, it's a selection of darkly realistic stories of people in his native city - and yet, as with all Joyce's writing, totally universal in its themes.

Ian McEwan's Nutshell is a murder story written from the point of view of the murderess's unborn child. Brilliant idea - and gripping! Tobias Wolff's Old School is a beautifully written reminiscence, by a student, of life at an American boarding school. If you liked the film Dead Poets Society or JD Salinger's Fanny and Zooey, you will love it. Then there was Borges' Labrynths. Had to read each paragraph several times to understand what he was saying; it's basically philosophy in the guise of short stories.

My bedside/fireside reading at this moment is: a book on the teachings of Edgar Cayce, the seer-channeller of Virginia Beach; Heart Advice of a Mahamudra Master, by Gendun Rinpoche (this never leaves my bedside, I read it over and over); and In Praise of Shadows by Junichiro Tanazaki, on the soulfulness of old Japanese houses and temples, where only the faint gleam of a gold wall hanging or the shine of black lacquer can be made out in the darkness.

This year I've tried to read more fiction, and these are some of the books I enjoyed.

Had never read James Joyce properly before, but Dubliners was a revelation. Written when he was in his twenties, it's a selection of darkly realistic stories of people in his native city - and yet, as with all Joyce's writing, totally universal in its themes.

Ian McEwan's Nutshell is a murder story written from the point of view of the murderess's unborn child. Brilliant idea - and gripping! Tobias Wolff's Old School is a beautifully written reminiscence, by a student, of life at an American boarding school. If you liked the film Dead Poets Society or JD Salinger's Fanny and Zooey, you will love it. Then there was Borges' Labrynths. Had to read each paragraph several times to understand what he was saying; it's basically philosophy in the guise of short stories.

My bedside/fireside reading at this moment is: a book on the teachings of Edgar Cayce, the seer-channeller of Virginia Beach; Heart Advice of a Mahamudra Master, by Gendun Rinpoche (this never leaves my bedside, I read it over and over); and In Praise of Shadows by Junichiro Tanazaki, on the soulfulness of old Japanese houses and temples, where only the faint gleam of a gold wall hanging or the shine of black lacquer can be made out in the darkness.

As someone who prefers Stygian gloom and softly glowing light over brightness, I love this time of year in the Northern Hemisphere when it gets dark around 4 o'clock and you have a long evening ahead of chatting, reading, watching a film or just thinking. After the hard work of the year I will be enjoying some festive celebrations with friends and family and retreating to my Winter cave.

Kind regards,

Tom Butler-Bowdon

Buy my books

On Amazon

Find me

Butler-Bowdon.com

Twitter

Facebook

Instagram

Comments and questions - Just reply to this email

Share & subscribe

Share this newsletter as a link

Subscribe to this newsletter

Kind regards,

Tom Butler-Bowdon

Buy my books

On Amazon

Find me

Butler-Bowdon.com

Comments and questions - Just reply to this email

Share & subscribe

Share this newsletter as a link

Subscribe to this newsletter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed