The writing

Just finished writing another book - well, the first draft anyway. A rewarding and fascinating few months, and with a tight deadline it was pretty intense towards the end.

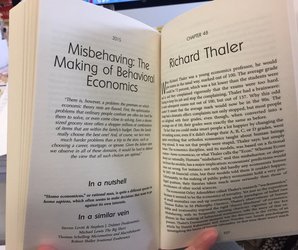

Now comes the editing, which involves: 1) the commissioning editor's initial judgement - fortunately, she liked what she read; 2) a copy editor marking up the document of 100,000+ words with highlighted mistakes and queries - see the example to your left from a chapter on Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century in 50 Economics Classics; and 3) the manuscript going into 'proofs', which is the page layout you see when the book is published, and which gives me a final chance to make corrections.

These stages mean that by the time you read the book, I've read it through at least four times. A bit laborious, but it doesn't mean mistakes and typos don't get through - for example, we somehow left out the author bio page in 50 Economics, which is in every other title in the series, and in the original edition of 50 Spiritual Classics I confused GI Gurdjieff follower Kathryn Mansfield, a Kiwi poet, with the film star Jayne Mansfield! - but luckily advances in the printing industry means you can do quick reprints (with corrections) more often.

What have I just written? A couple of years ago I sent out a survey asking people what subject they would most like to see featured in the 50 Classics series. Top was philosophy, which was duly covered; second was business, so there's a hint of what's coming in 2018.

Just finished writing another book - well, the first draft anyway. A rewarding and fascinating few months, and with a tight deadline it was pretty intense towards the end.

Now comes the editing, which involves: 1) the commissioning editor's initial judgement - fortunately, she liked what she read; 2) a copy editor marking up the document of 100,000+ words with highlighted mistakes and queries - see the example to your left from a chapter on Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century in 50 Economics Classics; and 3) the manuscript going into 'proofs', which is the page layout you see when the book is published, and which gives me a final chance to make corrections.

These stages mean that by the time you read the book, I've read it through at least four times. A bit laborious, but it doesn't mean mistakes and typos don't get through - for example, we somehow left out the author bio page in 50 Economics, which is in every other title in the series, and in the original edition of 50 Spiritual Classics I confused GI Gurdjieff follower Kathryn Mansfield, a Kiwi poet, with the film star Jayne Mansfield! - but luckily advances in the printing industry means you can do quick reprints (with corrections) more often.

What have I just written? A couple of years ago I sent out a survey asking people what subject they would most like to see featured in the 50 Classics series. Top was philosophy, which was duly covered; second was business, so there's a hint of what's coming in 2018.

We can change, right

As well as books written on contract, I also have personal writing projects that are more long-term or speculative. As part of one of them, this week I've been devouring the German philosopher Peter Sloterdjik's You Must Change Your Life, which imagines human beings as a striving species that is continually working to better itself - either through spiritual, ascetic practices, or through secular physical training or personal development. The title comes from Rainer Maria Rilke's poem ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’, which has an observer taking in the headless stone torso of the Greek god in the Louvre museum. Struck by the power and athleticism of the figure, the observer suddenly sees his own, insufficient existence. The poem ends with the famous line, You must change your life.

This impulse for improvement or transformation is behind all my books. Writing the first three, 50 Self-Help Classics, 50 Success Classics, and 50 Spiritual Classics, I was often so taken by the great titles I was reading that I kept the book covers face down - such was their power.

These three books together celebrate what Sloterdjik calls Homo artista, or the "human in training". As a member of this striving, self-improving species, I wanted to find the best ideas from each of these realms, for myself as much as the reader.

Later this week is the release of a new edition of 50 Self-Help Classics, a new edition of 50 Success Classics, and the rerelease of 50 Spiritual Classics, all with lovely new covers and in Kindle e-book.

As well as books written on contract, I also have personal writing projects that are more long-term or speculative. As part of one of them, this week I've been devouring the German philosopher Peter Sloterdjik's You Must Change Your Life, which imagines human beings as a striving species that is continually working to better itself - either through spiritual, ascetic practices, or through secular physical training or personal development. The title comes from Rainer Maria Rilke's poem ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’, which has an observer taking in the headless stone torso of the Greek god in the Louvre museum. Struck by the power and athleticism of the figure, the observer suddenly sees his own, insufficient existence. The poem ends with the famous line, You must change your life.

This impulse for improvement or transformation is behind all my books. Writing the first three, 50 Self-Help Classics, 50 Success Classics, and 50 Spiritual Classics, I was often so taken by the great titles I was reading that I kept the book covers face down - such was their power.

These three books together celebrate what Sloterdjik calls Homo artista, or the "human in training". As a member of this striving, self-improving species, I wanted to find the best ideas from each of these realms, for myself as much as the reader.

Later this week is the release of a new edition of 50 Self-Help Classics, a new edition of 50 Success Classics, and the rerelease of 50 Spiritual Classics, all with lovely new covers and in Kindle e-book.

Help yourself

Almost 15 years have passed since 50 Self-Help Classics was published. What, if anything, has changed in the self-help field? Many would argue that the genre has been superseded by psychology and its more scientific approach to understanding why we think and act as we do. Indeed, when I wrote about Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence and Martin Seligman’s Learned Optimism, such titles were a sign of things to come in terms of personal development becoming more grounded and scientific. A person who, 20 years ago, might have been happy to get a lift or a set of life pointers from How to Win Friends and Influence People, today might be drawn to a book by Daniel Kahneman (Thinking, Fast and Slow).

There is still a place for great self-help writing, although it is more likely to support its claims by reference to research. Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit and Brené Brown’s Daring Greatly are good examples. Yet self-help books can offer something that goes beyond psychology. David Brooks’ The Road to Character is really a work of ethical philosophy with a powerful message about personal change across a lifetime. Marie Kondo’s deceptively simple The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up aims to transform our life through changing our attitude to things and spaces; if our homes have the air of a Shinto shrine, peace, order and happiness reign.

What self-help books do well is combine aspects of different areas, including psychology, philosophy, spirituality, motivation and even business (see, for example, Clayton Christensen’s How Will You Measure Your Life?) to create an intimate connection with the reader. You really can change your life, the authors tell us, and here's how.

The second edition of 50 Self-Help Classics includes new chapters on the above titles. The genre is as fascinating and inspiring as ever.

Almost 15 years have passed since 50 Self-Help Classics was published. What, if anything, has changed in the self-help field? Many would argue that the genre has been superseded by psychology and its more scientific approach to understanding why we think and act as we do. Indeed, when I wrote about Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence and Martin Seligman’s Learned Optimism, such titles were a sign of things to come in terms of personal development becoming more grounded and scientific. A person who, 20 years ago, might have been happy to get a lift or a set of life pointers from How to Win Friends and Influence People, today might be drawn to a book by Daniel Kahneman (Thinking, Fast and Slow).

There is still a place for great self-help writing, although it is more likely to support its claims by reference to research. Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit and Brené Brown’s Daring Greatly are good examples. Yet self-help books can offer something that goes beyond psychology. David Brooks’ The Road to Character is really a work of ethical philosophy with a powerful message about personal change across a lifetime. Marie Kondo’s deceptively simple The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up aims to transform our life through changing our attitude to things and spaces; if our homes have the air of a Shinto shrine, peace, order and happiness reign.

What self-help books do well is combine aspects of different areas, including psychology, philosophy, spirituality, motivation and even business (see, for example, Clayton Christensen’s How Will You Measure Your Life?) to create an intimate connection with the reader. You really can change your life, the authors tell us, and here's how.

The second edition of 50 Self-Help Classics includes new chapters on the above titles. The genre is as fascinating and inspiring as ever.

Success manual

The success genre continues to develop as well. One thing that has changed since the first edition is that strategies for success, which were once the preserve of folk wisdom, parents, bosses, and motivational speakers, have become the subject of mainstream academic research. Two great examples, which I include in this new edition, are psychologist Angela Duckworth’s investigation of the concept of ‘grit’, which tells us much about what makes people successful irrespective of intelligence, grades, or even life circumstances, and organizational psychologist Adam Grant’s research into the long-term benefits of being a ‘giver’ in the workplace, which contradicts the idea that success comes from selfish ambition.

I also wanted to go beyond tips, ideas and advice to cover theories of success. Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers: The Story of Success has been important in the way it goes beyond pat explanations of the ‘self-made’ person to offer a more well-rounded environmental, social view of how success happens. And yet, I believe that Gladwell goes too far in reducing the role of human agency and free will. The fact that life is not just about good opportunities, but having the guts or wisdom to seize them, despite the waves they can create, is really the essence of success.

Indeed, it is hard to go past the truth of Carl Jung’s thought:

“In the last analysis, the essential thing is the life of individual. This alone makes history, here alone do the great transformations take place, and the whole future, the whole history of the world, ultimately springs as a gigantic summation from these hidden source in individuals.”

My hope is that the combination of psychological science and success philosophy, combined with close observation of how people advance in real life, will result in a discipline of success (in the way that, for instance, management became a discipline). 50 Success Classics is one contribution toward that.

The success genre continues to develop as well. One thing that has changed since the first edition is that strategies for success, which were once the preserve of folk wisdom, parents, bosses, and motivational speakers, have become the subject of mainstream academic research. Two great examples, which I include in this new edition, are psychologist Angela Duckworth’s investigation of the concept of ‘grit’, which tells us much about what makes people successful irrespective of intelligence, grades, or even life circumstances, and organizational psychologist Adam Grant’s research into the long-term benefits of being a ‘giver’ in the workplace, which contradicts the idea that success comes from selfish ambition.

I also wanted to go beyond tips, ideas and advice to cover theories of success. Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers: The Story of Success has been important in the way it goes beyond pat explanations of the ‘self-made’ person to offer a more well-rounded environmental, social view of how success happens. And yet, I believe that Gladwell goes too far in reducing the role of human agency and free will. The fact that life is not just about good opportunities, but having the guts or wisdom to seize them, despite the waves they can create, is really the essence of success.

Indeed, it is hard to go past the truth of Carl Jung’s thought:

“In the last analysis, the essential thing is the life of individual. This alone makes history, here alone do the great transformations take place, and the whole future, the whole history of the world, ultimately springs as a gigantic summation from these hidden source in individuals.”

My hope is that the combination of psychological science and success philosophy, combined with close observation of how people advance in real life, will result in a discipline of success (in the way that, for instance, management became a discipline). 50 Success Classics is one contribution toward that.

Enlightening read

The third in the personal development trilogy was 50 Spiritual. Getting into the minds of people like Teresa of Avila, Herman Hesse and Paramahansa Yogananda was an amazing thing, and while writing it I had some spiritual experiences myself. One would think you could only have such experiences while meditating or praying or being in nature - but no, it can come simply while reading a book.

This is not a new edition as such, just has a new cover, but if you feel ready for a book like this it is a good entry point. It spans the thinking of all the great religions, but also novelists including Somerset Maugham and New Age writers including Neale Donald Walsch, Marianne Williamson and Eckhart Tolle.

The third in the personal development trilogy was 50 Spiritual. Getting into the minds of people like Teresa of Avila, Herman Hesse and Paramahansa Yogananda was an amazing thing, and while writing it I had some spiritual experiences myself. One would think you could only have such experiences while meditating or praying or being in nature - but no, it can come simply while reading a book.

This is not a new edition as such, just has a new cover, but if you feel ready for a book like this it is a good entry point. It spans the thinking of all the great religions, but also novelists including Somerset Maugham and New Age writers including Neale Donald Walsch, Marianne Williamson and Eckhart Tolle.

Misbehaving

I included a chapter on Richard Thaler's Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics, in 50 Economics Classics, along with commentaries on all the great names in the discipline, from Adam Smith to Thomas Piketty to Elinor Ostrom to Paul Krugman. As you've probably heard, Thaler has won the 2017 Nobel Prize for economics, or in this case behavioral economics, which blends insights from psychology with economic stuff to give us a more realistic picture of how people make decisions, and how economies work in the real world, not just in theory. According to orthodox economics, people are rational, and 'misbehave' when they don't act in their own best interests. But as Thaler's work notes, that is something we do all the time.

I included a chapter on Richard Thaler's Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics, in 50 Economics Classics, along with commentaries on all the great names in the discipline, from Adam Smith to Thomas Piketty to Elinor Ostrom to Paul Krugman. As you've probably heard, Thaler has won the 2017 Nobel Prize for economics, or in this case behavioral economics, which blends insights from psychology with economic stuff to give us a more realistic picture of how people make decisions, and how economies work in the real world, not just in theory. According to orthodox economics, people are rational, and 'misbehave' when they don't act in their own best interests. But as Thaler's work notes, that is something we do all the time.

If you've seen the film The Big Short, about the 2007-09 financial crisis and how it happened (based on Michael Lewis' book, which I also cover), you will have seen Thaler himself in a cameo.

The scene is a casino, where he explains the "hot hand" fallacy. Good film, but the book The Big Short is even better.

The scene is a casino, where he explains the "hot hand" fallacy. Good film, but the book The Big Short is even better.

In the stacks

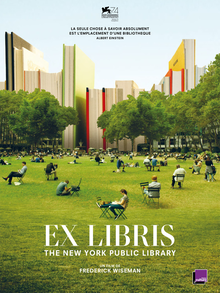

What is the role of a library in a time when it is so easy to download just about any book?

In fact, as I've discovered, there are millions of titles which have not been scanned or are not available in e-book form. But beyond that, libraries are a place that people go to elevate themselves, either their mood or their mind, or both.

Yesterday I was in the The British Library, which was packed - not just the hundreds in reading rooms, but many more people sprawled around the lobby area and cafes using the free wifi and generally enjoying the atmosphere of learning. People know that libraries are not just a store of knowledge but a symbol of civilization, and they want to be part of that.

This week in the mail came an invite to a ceremony for the $1 million Berggruen Philosophy Prize at the New York Public Library. Sadly I cannot go, but I see there's a new film, Ex Libris: The New York Public Library, by the esteemed documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman. It won a prize at the Venice Film Festival this year, and has just been showing at the London Film Festival. Here's a review in the New York Times. Can't wait to see!

Kind regards,

Tom

p.s. I've written my first online course, "Great Modern Philosophers", which you can find on Highbrow. It's based on 50 Philosophy Classics and covers ten great minds in brief, including Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre, Wittgenstein, Kierkegaard and more. Have a look!

Find me

Butler-Bowdon.com

Twitter

Facebook

Instagram

Email

Share & subscribe

Subscribe to Theory of Success

What is the role of a library in a time when it is so easy to download just about any book?

In fact, as I've discovered, there are millions of titles which have not been scanned or are not available in e-book form. But beyond that, libraries are a place that people go to elevate themselves, either their mood or their mind, or both.

Yesterday I was in the The British Library, which was packed - not just the hundreds in reading rooms, but many more people sprawled around the lobby area and cafes using the free wifi and generally enjoying the atmosphere of learning. People know that libraries are not just a store of knowledge but a symbol of civilization, and they want to be part of that.

This week in the mail came an invite to a ceremony for the $1 million Berggruen Philosophy Prize at the New York Public Library. Sadly I cannot go, but I see there's a new film, Ex Libris: The New York Public Library, by the esteemed documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman. It won a prize at the Venice Film Festival this year, and has just been showing at the London Film Festival. Here's a review in the New York Times. Can't wait to see!

Kind regards,

Tom

p.s. I've written my first online course, "Great Modern Philosophers", which you can find on Highbrow. It's based on 50 Philosophy Classics and covers ten great minds in brief, including Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre, Wittgenstein, Kierkegaard and more. Have a look!

Find me

Butler-Bowdon.com

Share & subscribe

Subscribe to Theory of Success

RSS Feed

RSS Feed